Unrivalled Support for C&C

Click logo to return to 'links-page'

Click logo to return to 'links-page'

Two visionary videos on 'transformational change' from top medics advocating C&C.

Philip Hanlon on the Good, the Beautiful and the True

It is now clear that the scarcest resource is the capacity of our atmosphere to continue to absorb the growing volume of CO2 and other GHG that we generate. How should we allocate this scarce resource? Should it be on the basis of where we are now, which confirms the status quo and the associated power of the big polluters? Or should we opt for a fairer, more radical approach, in which all people around the world are deemed to have an equal stake in the atmosphere, and hence rights in and responsibilities for the future of our planet? This is the key principle underlying 'Contraction and Convergence' proposals for managing global warming. In the current global setting, is it better to pitch high for an equity-based solution, or go for the second best, which is more in tune with the current power balance?

The political philosopher John Rawls outlined a theory of distributive justice, which sought to promote 'justice as fairness'. He argued that people are likely to develop the ideal set of rules and institutions if they start from a point where no rules currently exist - a situation Rawls calls the 'original position' - and with the goal that any new rules are based on equal basic liberties for all. The rules will also be fairest if they are drafted by people acting as though they are behind a 'veil of ignorance' and do not yet know where they will be in the future economic and political hierarchy. Rawls's hypothesis is that by applying these principles, people are likely to construct a society based on rules that deliver the best possible outcome for everyone.

Climate Change In Africa

Camilla Toulmin IIED

In a recent paper in The Lancet we propose that the world should commit to reducing the global average daily intake of meat, especially red meat from ruminants. This would be part of the evolving portfolio strategy – across various sectors of commerce, energy use and human behaviour – to mitigate climate change. The fairest approach is ‘contraction and convergence’, where the world’s nations agree to reduce average per-person meat consumption (currently just over 100 grams per day) and to do so equitably. High-consuming populations would reduce their intake and low-consuming populations could increase their intake up to the agreed average level.

Contraction and Convergence is Good for our Health

Food Ethics - Tony McMichael

UNESCO COMEST on C&C

"The principle of contraction & convergence refers to the emission of gases contributing to the greenhouse effect. A fair and pragmatic approach, it is argued, would be to move gradually towards quotas that would not be indexed on GOP, as is the case in the Kyoto Protocol, but rather on population, while gradually reducing the permitted total towards the 60% reduction commended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Such a principle may be seen as a consequence of both the principles of environmental justice and the principles of earth as global commons. The particular problem whether future emissions allocations should be based on a per capita basis, as the so-called “contraction and convergence” proposal suggests, or on a country basis, might be seen in a different light if humanitarian aid were internationally organized on a basis of each country’s ability to pay. The greater duty of rich countries to contribute to such aid might be politically easier to accept than more stringent emission limits imposed on “more polluting” and “past polluting” countries than LDCs (least developed countries), which would also cost “richer” countries more."

Contraction and Convergence (C&C) is the science-based, global climate policy framework proposed to the United Nations since 1990 by the Global Commons Institute (GCI).

See http://www.gci.org.uk/briefings/ICE.pdf

UNESCO - The Ethical Implications of Climate Change: A Report by the

World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (COMEST)

Along with Human Well-Being and Economic Decision-Making, we have to ask about “green taxes” that will check environmental irresponsibility and build up resources to address the ecological crises that menace us. The Contraction and Convergence proposals are among the best known and most structurally simple of these, and it would be a major step to hear some endorsement of them from a body such as this.

Faith and the Global Agenda: Values for the Post-Crisis Economy

World Economic Forum, DAVOS, Switzerland 2010

"'When one looks at the kinds of reductions that would be required globally, the only means for doing so is to ensure that there's Contraction and Convergence and I think there's growing acceptance of this reality. I don't see how else we might be able to fit into the overall budget for emissions for the world as a whole by 2050. We need to start putting this principle into practice as early as possible'."

Rajendra Pachauri Chairman IPCC

Global Humanitarian Forum 2008

"As with all great ideas, C&C is deceptively simple, addresses the root causes of the problem, and is recognized as a grave threat to those vested interests who fear the climate change problem’s successful resolution because of the fundamental changes it will wrought on our economic status quo. The sustained effort of GCI over 20 years is a testimony to Aubrey's integrity, commitment, and resolve. The logic and calculus of C&C is inescapable once an objective analysis is undertaken. For years, it was foolishly dismissed as impractical! Somewhat ironically, those who now view the problem with a clear head are increasingly accepting that C&C presents the only politically acceptable solution to the foundational question of how the permissible emissions can be distributed amongst the people of Earth."

Professor Brendan Mackey Australia National University

Winning the Struggle Against Global Warming

What Will It Take? The Earth Charter Global Dialogue on Ethics and Climate Change

Brendan Mackey and Song Li

Protecting Life from Climate Change

The need for synergies between policy, ethics, and education - David Chalmers

Contraction and Convergence

Capping greenhouse gas emissions globally is indispensable for maintaining the integrity of life on the planet. Sixty percent in six decades is roughly the order of magnitude contraction requires. However, the Kyoto Protocol so far fails to live up to this challenge. It does not demand serious reductions from the North, and does not include newly industrializing countries from the South. Nevertheless, for the second commitment period of the Kyoto process, an ecological breakthrough cannot be reasonably expected unless the South assumes commitments as well. Otherwise, the North will stall, and, more importantly, the steep rise in emission levels in the South will continue unchecked. At this point, the issue of equity will reveal itself as the major bottleneck for any serious progress in climate protection. On the one side, the South will refuse obligations before the North follows through on its responsibility, while on the other side the North will not be forthcoming before commitments for the South are defined. Unless the reduction commitments of the North and those of the South are balanced out in fairness, no real climate protection will happen. Only a framework that respects the principle of equal per capita right to the resources of this Earth will eventually hold up to equity and fairness. Any other allocation scheme (”grandfathering”, ”cost-base ”) would repeat a colonial constellation of granting disproportionate shares to the North. If the use of the commons has to be restrained through common rules, it would violate the principle of equity to design these rules to the advantage of some and the disadvantage of many. The equal right of all world citizens to the atmospheric commons is therefore the cornerstone of any viable climate regime. Therefore, for the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, a process allocating emission allowances based on per capita equal rights to each country, has to be initiated. This is hard on the North, but not unfair as in exchange for accepting the rule of egalitarianism in the present, industrial countries would not be held liable for emissions accumulated in the past. It is from this right to atmospheric commons that all countries (and all classes) in the long run converge in their trajectories upon a similar level of fossil energy use per capita. The North contracts downwards, and the South converges upwards. Over-users will have to climb down from the present level, while under-users are permitted to raise their present level, albeit at a gradient that is much less than the one industrial countries went through historically, levelling off at the point of convergence. However, the convergence of North and South on equal emission levels cannot be achieved at the expense of contraction, i.e. the transition to globally sustainable levels of emissions. Once again, sustainability gives shape to equity. The vision of ”contraction and convergence” combines ecology and equity most elegantly; it starts with the insight that the global environmental space is finite and attempts to fairly share its permissible use among all world citizens taking into account the future generations as well.

The Jo'burg Memo

Heinrich Boell Foundation

" . . . More countries might be willing to agree to Contraction and Convergence from the outset than to the supplementary system, while developing countries might agree to join the former in view of the desperate need for a climate change agreement and of the prospect of the supplementary system being introduced in its wake, once international co-operation about mitigation and adaptation was in place. Hence a system of Contraction and Convergence probably remains the best prospect for addressing the global problems of mitigation and adaptation, and at the same time a promising spring-board for achieving a global agreement on addressing the problems of poverty and under-development of the kind that is also urgently needed."

Human Ecology Review 2010

Robin Attfield

Context Analysis - Ethics and international climate policy

The recent UN conference on climate policy at Copenhagen highlighted fundamental problems in the framing of climate policy debates and in the integration of ethical, social and behavioural factors in the development of policy:

- Explicit normative framings of the issues at stake were presented by various groups - such as the alliance of small island states, and the numerous NGO campaigners meeting alongside the Conference of the Parties. These positions emphasised arguments that assign ethical responsibility primarily to the industrialised countries to take urgent action for mitigation, assistance in adaptation to developing countries, and so on;

- The Kyoto framework assumes and includes an ethical stance in which primary responsibility for emissions reduction falls on the industrialised countries, via the policy of common but ‘differentiated’ responsibilities among nations;

- Alternative frameworks proposed for mitigation - such as Contraction and Convergence (Meyer, 2000) - also represent distinctive ethical stances, emphasising the need for and right to increased energy use for development for the poor world, with attendant demands for change in industrial world consumption patterns as a matter of perceived social and ecological justice;

- The complex ethical dimensions of climate change mitigation and adaptation, in particular those relating to contested ideas of justice and responsibility, were not highlighted in the Copenhagen conference’s final outputs. Nevertheless, positions that are unarguably ethical in the neutral descriptive sense - and often problematic – were present throughout the negotiation in multiple contexts;

“Contraction and Convergence’, has 3 main components: -

- each person on the planet is granted an equal right to emit carbon by virtue of their equal right to use the benefits provided by a shared atmosphere. This principle is treated as intrinsic to the architecture of the approach and not a longer-term aspiration as in the case of Kyoto Plus.

- a ‘global ceiling ‘ for greenhouse emissions is set based on a calculation of the amount the global environment can withstand without dangerous climate change taking place.

- each country is allocated a yearly ‘carbon emissions budget ‘ consistent with the global ceiling not being exceeded, and calculated according to each country’s population size relative to an agreed base year. The name of the approach comes from the notion that over time, it aims to bring about a stabilisation, and later a contraction, in global greenhouse emissions so that they stay below a safe level; and that, in the longer term, developed and developing countries will converge on a roughly equal level of per capita emissions.

Within this overall approach, a country that wants to emit more than its yearly quota must buy credits from countries that have spare capacity. The country selling the credits is then free to invest the receipts in activities enabling it to develop sustainably. An emissions mechanism is a key feature of all of the proposed successors to Kyoto, but in this version the trading zone covers the whole planet from the outset. The consequence is that Contraction and Convergence offers a unique mixture of equity and flexibility which does not seek a literal convergence in greenhouse emissions, but rather a convergence in the rights of all countries to make use of the atmospheric commons. Unlike a number of competing approaches, Contraction and Convergence, if fully implemented and complied with, could be expected to reduce the risks of dangerous climate change substantially, although it will not prevent many adverse impacts in the short to medium-term. It also has the merit that it adopts emissions targets based on scientific criteria for protecting inequalities between developing and developed countries, and between generations, relative to its rivals. It will also tend to improve, relative to rival approaches, the position of the worst off since research suggests strongly that very many of the worst off will be members of developing countries in a future world blighted by climate change. Finally, it will be attractive to those who wish to bring as many people as possible to the point where they have enough since the measures it will introduce will benefit many millions of people in developed and developing countries who lead, or will lead, lives lacking in what is needed for a decent life without bringing more than a very limited number of people below the sufficiency level."

"Contraction and Convergence - the Global Solution to Climate Change" -

Aubrey Meyer Green Books. C&C was pioneered by the Global Commons Institute

Climate Change, Justice and Future Generations

Edward Page

"Colin Challen, chair of the All Party Parliamentary Climate Change Group in Britain, in a speech on March 28, 2006, called for the Contraction and Convergence plan of the Global Commons Institute based in the UK, (www.gci,org.uk), which calls for globally shared “emission rights" for every man, woman, and child, so that poorer people could sell theirs to the richer thereby converging on equitable reductions of CO2."

"Ethical Markets: Growing the Green Economy"

Hazel Henderson

"The best known rights-based approach to climate change mitigation is the 'contraction-and-convergence' (C&C) framework presented by the Global Commons Institute (GCI) at the second Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in 1996. The idea, very briefly, was to articulate a longterm mitigation strategy that, while reducing the overall amount of GHG in use over time, would also lend toward equalising GHG emissions per person on a global scale. In such a regime, as overall global emissions dropped, the fall would be more precipitate in wealthy countries, while usage in poorer countries would continue to rise for a period in line with their greater development needs - toward convergence between rich and poor countries at some point in the future. Initially GCI abjured the term ' rights' in reference to C&C, because they regarded the atmosphere as a global commons that 'cannot be appropriated by any state or person. Today, however, GCI claims that C&C 'establishes a constitutional, global-equal-rights-based framework for the arrest of greenhouse gas emissions. This new formulation appears to be in line with a general shift toward the language of rights in the climate change arena. Whereas the 'rights' at issue in models such as C&C amount to speculative universal 'rights to emit' GHGs, with no obvious basis in human rights law, they might be framed as deriving from the 'right to development', which is mentioned somewhat obliquely in the UNFCCC. Such a derivation would depend on demonstrating that 'subsistence emissions' were in fact required to achieve basic human rights, a claim that is at least plausible. The right to development is a difficult and somewhat confusing notion. In international law, it has had, since 1986, declaratory (non-binding) status, and has been a subject of protracted and sometimes polarising discussion within the United Nations. But whatever its doctrinal status, discussion of the right to development has evolved with time, albeit rather as a space for negotiating the differing interests of different parties in the international system rather than as law in the ordinary sense. For many, particularly in countries most vulnerable to climate change, it still provides a natural hook for assessing the rights implications of climate change and the policy premises that should underlie solutions."

Human Rights and Climate Change

Stephen Humphreys

Costs of emissions reductions will adversly impact the economies of some regions more than others. Dislocating coal jobs in the poorer regions will have a greater political-economic impact than on the wealthier coastal and urban regions where the energy from coal is primarily used. As Hu (2009) argues, it is the wealthier regions that need to make the reductions first, allowing interior and western regions to continue developing while the wealthier regions taken on the burden of beginning the process of contraction and convergence across sectors. In developing a national C&C roadmap, China’s governance will require a scalar methodology of oversight resembling the approach introduced as the climate box. Ensuring that this box is tightly sealed is a difficult problem for the Government, as emissions slippage will almost certainly occur at multiple levels. Furthermore, each of these scales of governance represents an opportunity for intervention by foreign governments, non-governmental organisations, firms and other parties that have an interest in seeing China converge its CO2 output and contract towards the nations fair share of global emissions. The primary challenges facing China will be on-site compliance and accountability of climate strategies, and the developments of more robust forms of public participation to ensure that they are measurably effective.

China’s Responsibility for Climate Change:

Ethics, Fairness and Environmental Policy - Paul Harris

The equal per capita option is certainly a live possibility. One of the most attractive versions is called “Contraction and Convergence” (C&C), and it rightly receives a lot of attention. As the name suggests, C&C is a model with two parts. The governments of the world begin by reaching agreement on some particular greenhouse-gas target: some global limit to emissions and a date by when this limit must be reached. C&C can then determine how quickly current emissions must contract in order to achieve the target. On the way to the target date, global emissions converge to equal per capita shares. The moral adequacy of this particular proposal depends on how its parts are cashed out. The Global Commons Institute, the largest advocate of C&C, makes a point of emphasizing what we have been calling the sustainability criterion: the greenhouse-gas budget we opt for ought to be tied to our best current scientific thinking, and it ought to be extremely risk-adverse. A large emphasis is not placed on historical responsibility, but certainly C&C requires larger burdens for faster and more substantial reductions on the part of developed countries. It does satisfy at least a large part of the present capacities and entitle-ments criterion, most obviously because ilt aims towards equal per capita emissions, but also because it allows for emissions trading. Whatever else it might do, emissions trading tends to narrow the gap between the rich and the poor. Finally, C&C is at least a long way down the road to procedural fairness. Rooted as it is in the notion that everyone has equal access to the atmosphere, there's just no room for either horse trading or bullying. From a moral point of view, C&C has a great deal to recommend it.

The Ethics of Climate Change Right and Wrong in a Warming World

James Garvey

"Fortunately, the nations of the world have signed the UNFCCC – the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This commits all nations to work together in solving the global warming problem. However, national governments now need to agree on a new protocol that commits everyone to reducing the total global emissions of greenhouse gases to a safe level. But what would such a new protocol look like?The answer is called Contraction and Convergence. "C&C" is a framework that forces governments to agree on three vital questions. First, what is a safe concentration of atmospheric greenhouse gases? Is it twice the current concentration? Half the current concentration? The present concentration? Many scientists argue a safe concentration is what it was during the 1960s. The fact is that the Earth system can absorb a certain amount of greenhouse gases without causing harmful change to the climate. So once a safe concentration is agreed upon, it is then easy to calculate the total global amount of greenhouse gas that can be emitted each year. The second question C&C forces governments to answer is, 'When will the total global emissions of greenhouse gases be reduced to the amount needed to maintain atmospheric concentrations at the agreed safe level?' In 2050? 2100? Next year? The sooner the better, of course, because the longer we wait the more harm is done to people and nature and the more expensive it becomes to fix the problem. The third important question a C&C framework would force governments to reach agreement on concerns how the permissible annual amount of greenhouse gas emissions will be allocated between nations. The simplest and fairest way is to give every person an equal share. This is called a per capita allocation, and is what C&C calls for. One important feature of C&C is that it treats nations fairly. Under this framework, the emission entitlement of people in a poor country will increase relative to what it is now, while that of people in a wealthy country will decrease. This is fair because historically poor countries have not caused the global warming problem and they need to now quickly develop to eliminate poverty. However, under a new C & C-framed protocol, all countries, including developing countries, will be committed to meeting their specified national greenhouse gas targets by the agreed date.

Once a new protocol is in place based on the C&C framework, national governments can then begin the difficult and complex task of negotiating their way through the various implementation issues - that is, working out how to most efficiently and fairly reduce emissions of greenhouse gases to the agreed safe level. In his report to the UK Treasury, Nicholas Stern, former Chief Economist of the World Bank, argued that international co-operation to solve the global warming problem must cover all aspects of policy to reduce emissions including pricing, technology, the removal of behavioural barriers, as well as action on emissions from land use. C&C does not solve all these problems, but provides a framework for their negotiated solution." Details on the Contraction & Convergence framework can be found at the web site of the Global Commons Institute.

"Winning the Struggle Against Global Warming

A Report to the Earth Charter International Council"

by Brendan Mackey and Song Li

"A Contraction and Convergence framework of global quotas has the potential to contribute highly to global justice. The recent “make poverty history” movement has demonstrated a moral awakening and a will among the affluent to see justice created worldwide. But with this, as with so many other things, individuals cannot create new systems. Global quotas can create new sytems and new forms of wealth and ensure that wealth is evenly pre-distributed to all citizens of the globe. The trading of quotas brings money to poor countries as a right, not as aid. By insisting on equity, Convergence addresses the objections of “less developed” economies to paying for the damage caused by the developed affluent communities. Poor and vulnerable countries and communities are most at risk from the climate change that results from global warming, even thought they are least responsible for causing the problem. And those who are already cash-poor have fewer immediate resources for escaping from or coping with the effects of climate change. Trading in quotas is a way to create a rights of greater social justice."

"Enough Is Plenty: Public and Private Policies for the 21st Century"

Anne B Ryan

WHOSE ATMOSPHERE?

The IPCC low concentration scenario results in a CO2 concentration of 450 ppmv CO2 and a total greenhouse gas concentration equivalent to about double pre-industrial levels. TIlis would produce a long.term temperature increase of about 2.5·C at the present best estimate of climate sensitivity. However, it is difficult to maintain that such a target would be tolerable with respect to the human rights of considerable sections of the world population. A lower target is required. taking into account not only the aggregate cost of dimate change mitigation, but also protection of the inalienable livelihood rights of la rge numbers of world cit izens. The Climate Action Network has therefore called for a target which keeps the global mean temperature increase below 2”C above pre·industrial levels, with the temperature being reduced as rapidly as possible after the time that it peaks. Such a target is unlikely to be ‘safe”, but the probability of a large scale dangerous change would be lowered for most regions. So far, both Northern and Southern governments - apart from the Island States - have shown little interest in defining low danger emission caps in the climate negotiations. All parties disregard the fact that when it comes to capping emissions, the choice is between human rights and the need for affluence. The task of keeping the temperature rise below 2’C appears too large, and too threatening to the economic interests of consumers and corporations. In particular, it still seems to have escaped the attention of Southern countries that dimate protection is of the utmost importance for the dignity and survival of their own people. It is time they become protagonists of climate protection, because climate protection is not simply aoout crops and coral reefs, but fundamentally aoout human rights. The point of convergence of North and South on equal emission levels cannot be achieved at the expense of contraction , i.e. the transition to globally sustainable levels of emissions. Once again, sustainability gives rise to equity.Indeed, the vision of "Contraction and Convergence” combines ecology and equity most elegantly; it starts with the insight that the global environmental space is finite, and attempts to fairly share its permissible use among all world citizens. taking into account the future generations as well.

Ethical Aspects of the Converntion on Climate Change

Wolfgang Sachs

It can be argued, if current generations in the developed countries claim sole ownership to the assets that they have inherited from prior generations, then they are also owners of the liabilities associated with those assets, and they are accountable for the excess use of the atmospheric commons by prior generations. As Bhaskar notes, "if I take an object, not knowing that it belongs to you, and give it to my daughter, you are surely entitled to reclaim it, even though neither my daughter nor I may be a thief" (1995, 116). Similarly, when one discovers that one has taken more than one's fair share, one is expected to make some form of reparation to the party or parties who were disadvantaged. Past practices of utilizing more than one's fair share of a common trust is not justification for continued bad behavior. To resolve these tensions, the contraction and convergence (C&C) response to climate change challenges seeks a global agreement on the concentration of atmospheric GHGs below which the planet's temperature will not rise more than two degrees Celsius, whether that concentration is set at 350,400 or 450 parts per million of CO2 , When this benchmark is set, the planet's carrying capacity for that concentration of GHGs can then be allocated to nations on a per capita basis. Those countries that are presently emitting more than their allotment (primarily the developed, industrialized countries) will be required to reduce their emissions (contraction) while those countries who are presently emitting less than their share (primarily developing countries) will be temporarily permitted to grow their emissions until, by an agreed date, all countries have reached their equal per capita entitlement (convergence) (den Elzen et al 2005). Developing countries might sell their surplus GHG shares during the adjustment phase which would presumably be completed by 2050 (Global Commons Institute 2008). For the C&C approach to become operational, the signatories to the UNFCCC must agree on a safe concentration of atmospheric GHGs, the proportional allocation of this limited capacity based on national populations, the fair assessment of current levels of emissions, targets for contraction of those national emissions that exceed allocations' and the concurrent temporary increase in emissions for those countries which have not utilized their full allocation - an enormous undertaking that has thus far been elusive (Bows & Anderson, 2008).' Nevertheless, the proponents of the C&C approach argue that it can provide an equitable and just response to the climate change challenge that can win the support of the developing world since it both protects their ability to develop and obligates the developed world to reduce its excess emissions (Global Commons Institute 2008). They further argue that the date of convergence should be realized as soon as possible since the most vulnerable and least responsible for climate change are currently bearing a disproportionate and unjust burden created by those who have utilized more than their fair share of the atmospheric commons, and justice demands that this be resolved as soon as possible.

Ethics the Environment

Victoria Davion University of Georgia

The issue of 'equity' broadens the policy discourse by including considerations not primarily motivated by the impacts of climate change and mitigation policies on global welfare as a whole, but rather by whether climate change and mitigation policics would exacerbate existing inequalities among and within countries. This is the basis for policy strategies that seek to promote greater equity in global use of resources by

allowing the emissions of developing nations to expand while overall global emissions are reduced. An important product of this is the 'contraction and convergence' approach in which the pursuit of greenhouse gas stabilization drives convergence of per capita emissions and income. This focus has led from considerations of equity towards an agenda of sustainable development.

Ethics, equity, and international negotiations on climate change edited

Luiz Pinguelli Rosa, Mohan Munasinghe

"One increasingly popular proposal for action on climate change involves 'contraction and convergence' (Meyer 2000) which calls for per-capita emissions of each state to be brought to a level that is equal with other states and that the atmosphere can withstand, in practice meaning that emissions in wealthy countries would come down to a safe level (contraction) and in most developing countries would go up to that level (convergence). The notion of contraction and convergence is essentially based on egalitarianism (Heyward 2007: 526). The equal per-capita amount that the atmosphere can withstand is roughly l .5 tonnes carbon-dioxide equivalent per person per year, which compares with about 20 tonnes in the United States, on one end or the spectrum, and about 0.1 tonnes in Mali, on the other (Smith 2006: 97). What the cosmopolitan corollary would require is that this policy be implemented not only among states but within them as well. This would mean that while most people in rich countries would lower their greenhouse gas emissions to the globally safe per-capita level most people in poor countries would be allowed to increase their emissions to that level. A difference between this approach and international doctrine is of course that poor people in wealthy states would not bear an unfair burden. Conversely, while most people in poor and developing countries would be allowed to increase their greenhouse gas emissions to the globally safe level, a large minority of people - the affluent - in those same countries would be required to reduce them. The precise amounts set for people would reasonably and fairly depend on their circumstances. Some people are in no position to reduce their emissions, and some emissions over the safe per capita limit might be allowed for certain people if there is no alternative. At the same time, it is reasonable and probably necessary to expect some people to reduce their emissions below the globally safe level. The candidates for this requirement will be those who have polluted far more than they should have done already and who have the means (financial technological and so forth) to reduce their emissions below the globally safe level while still meeting their basic needs."

World Ethics and Climate Change: From International to Global Justice

Paul G Harris

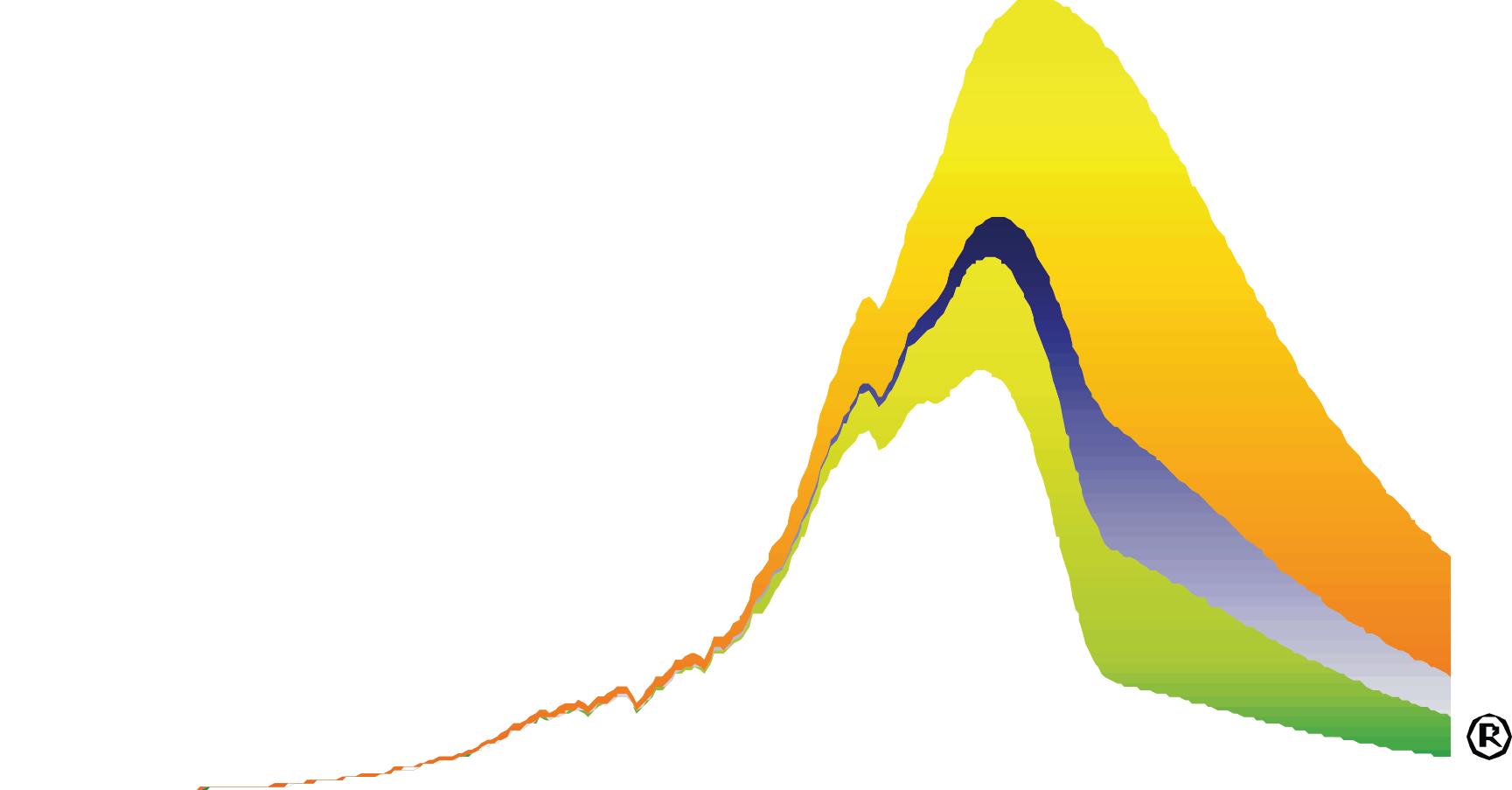

"Per capita emissions allocated according to Contraction and Convergence [2030 convergence year] under an emissions pathway designed to stabilize atmospheric GHG concentrations at 450 ppmv CO2 equivalent."

Climate Ethics

Henry Shue

"One widely discussed and advocated framework for tackling climate change which claims a strong foundation in this mythic position of climate change as social justice is that of 'Contraction-and-convergence' (Meyer. 2001). Contraction-and-convergence has been widely endorsed by organizations ranging from the international negotiating bloc of the Africa Group, the Church of England, and from individuals such as Germany's Chancellor, Angela Merkel. The Indian Prime Minister has repeatedly stressed this principle when articulating the negotiating position of his country in international negotiations: 'Longterm convergence of per capita emissions is ... the only equitable basis for a global compact on climate change' (Singh. 2008)."

The Future of Ethics

Stefan Skrimshire

"This approach is given the name of contraction and convergence as articulated by Aubrey Meyer of the Global Commons Institute."

A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming

Michael S. Northcott

"This is what the White Paper favours a particular interpretation of the principle by Aubrey Meyer, the contraction and convergence account in which there would be contraction of the total emissions and convergence to equal human entitlements."

Creation, Environment and Ethics

Rebekah Humphreys (Author, Editor), Sophie Vlacos

"South African musician Aubrey Meyer has secured the support of several countries and international agencies for his “Contraction and Convergence” strategy to tackle the fundamental causes of global warming.”

Ethics in Small and Medium Sized Enterprizes

Laura J Spence

For excellent discussion of the rights of future people see Meyer 2003

Climate Change, Ethics and Human Security [Hardcover]

Karen O’Brien, Asunción Lera St. Clair, Berit Kristoffersen

Because of the long phase-in time that would be required to move toward per capita allocations in the developed nations. those developing nations pushing for per capita allocation have proposed an approach usually re ferred to as ·'contraction and convergence’. Contraction and convergence means an allocation that would allow the large emitter nations long enough time, perhaps thirty or forty years to contract their emissions through the replacement of greenhouse gas-emitting capital and infrastructure and eventually converge on a uniform per capita allocation. Support for contraction and convergence has been building around the world with the European Parliament in 1998 recently calling for its adoption with a 90 percent majority. A per capita allocation would be just for the following reasons:

• It treats all individuals as equals and therefore is consistent with theories of distributive justice .

• It would implement the ethical maxim that all people should have equal rights to use a global commons.

• It would implement the widely accepted polluter-pays principle

American heat: ethical problems with the United States’ response to global warming

Donald A. Brown.

One suggestion made by a variety of different people is that each person has a right to emit an equal amount of greenhouse gases. This view then takes an egalitarian approach to the distribution of one kind of energy right. This view is remarkably popular. It was for example expressed by Anil Agarwal in their Global Warming in an Unequal World. It also underpins the proposal known as Contraction and Convergence which has been developed and defended by the Global Commons Institute.

The Ethics of Global Climate Change

Denis G. Arnold

Contraction and Convergence - one of the most interesting concepts for a contract for peoples’ CO2 justice is currently being discussed under the title Contraction and Convergence [C&C]. Here, a contract of a global CO2 emissions allowable limits in advance [contraction] is proposed with a process of gradually approximating a distribution of emission allowances to egalitarian criteria [convergence].

Principle of sustainability: A draft of theological and ethical perspective

Markus Vogt

Equity and fairness concerns are reflected in the Framework Convention itself. Equity is considered explicitly in many of the proposals for a post-Kyoto climate agreement, perhaps most prominently the Contraction and Convergence proposal, put forward by the Global Commons Institute, see: -

Fairness in International Climate Change Law and Policy

The Priority of National and International Agreements

Much discussion about climate change ethics is conducted in what may be called an "internationalist” context, It is about nalion-states (which I shall call states), and what states have contributed in the past to emissions what their contribution is now, what each state should do, what international agreements need to be made, what principles ought to guide these agreements and so on. The rationale is partly cosmopolitan in that at least some of the drive to reach agreements to cut GHG emissions arises from concern for the long-term prospects for living conditions of human beings anywhere, (of course there are other motives as well: not least concern for the future wellbeing of people within one’s own state). Much attention is devoted to identifying ethical principles, sometimes stated as principles of global justice, for determining what eaeh state should do, and to pragmatic principles that could bc the basis for agreements, such as ‘contraction and convergence’ and ‘greenhouse development rights’.

Ethics and Global Environmental Policy

Paul Harris

.